Ambahan about sickness and death

Ambahan about sickness and death

In ancient, pre-Spanish Philippines, reading and writing were ubiquitious rather than for the elite or religious class. Writing was not for government texts or religious scripture but for personal letters and love poems. (more about Baybayin script here)

An ambahan is an indigineous Filipino poetic form of heptasyllable lines. Themes of this poetic form covered all stages of life, included sickness and death. This poem about death touched me as exquisite (Ambahan number 246 from Postma’s “Treasure of a Minority”):

| Hanunoo-Mangyan: | Tagalog: | English (Postma’s translation): |

| Magkunkuno ti karadwa Kang kis-ab mag-iginan Ginan kang tipit lingban Apwan mambon mambu-nan Babaw apnig bariwan Ud paway sa gihitan Halaw nangitlagan wan Kasanggaling sa siknan Kahabog sa ulangan Taghilyan di kumon wan Kang apwan sa humagan Manrikuyan manrigsan Sa danom magka-uman Bag-o paligbuyungan Kan bansay nag-abyagan Kan suyong nalan-ganan |

Taghoy ng kaluluwa: Kanina nang lumisan Sa dampa kong tahanan Katawan ko’y naghihirap Sa banig na higaan Di pa lumilisan Balisang nagpaalam Pa-biling-biling naman Pakaliwa’t pakanan Sige na nga kung ganyan Ako na ay lilisan Liligo sa hugasan Sa tubig dalisayan Sa bago kong hantungan Sa tabihan ni Amang Kapiling na si Inang! |

Says the soul remembering: Just a while ago at home, in the house I used to stay, My body was really bad, lying sickly on the mat, though not ready yet to go. Scared to death I really was! I was going to the right and to left, back and forth! So confused I was that time! Now, my body laid at rest, finally I took a bath in the waters for the soul. I am starting on my way to the place my father went, & where mother joined him, too. |

Fining-pot

Many ambahans begin with a “who is speaking” (magkunkuno) line. In this case it is the soul of one who recently died. The soul remembers his or her body becoming sick. It is unclear what the cause was however the moving of the body to the right and left, and back back and forth suggest convulsions from seizures or fever from an infection (or both). Confusion may also suggest delirium (which is very commonly seen in the sickest of patients in the hospital and ICU) as well as the emotional and spiritual distress that comes with dying.

The poem then takes a turn (like kireji or volta) when the soul describes the body being buried. Postma translates the body “being laid at rest” and then taking a “bath in the waters for the soul.” I believe Postma, who married and lived among the Hanunoo (tribe in the Philippines), must have had further insight into the meaning of these lines. The Tagalog translation also took interesting choices in translation of the Hanunoo-Mangyan language.

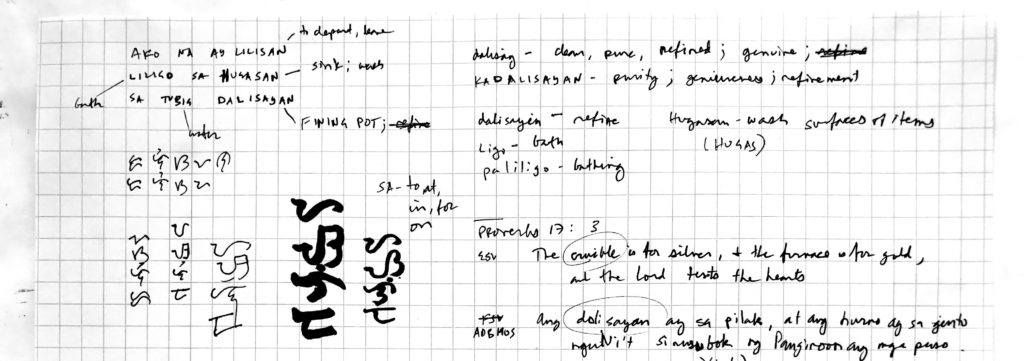

- “lilisan”

- According to multiple dictionaries: Lilis: (n) ruffle, fold, rolled sleeve; Lilisan: (v) to depart, to leave; Maglilis: (v) to tuck.

- “tubig dalisayan”

- Tubig unambiguously means water.

- According to multiple dictionaries: Dalisayan: (n) fining-pot; Dalisay: (adj) genuine, pure, clean, refined; Dalisayin: (v) to cleanse, to refine; Kadalisayan: (n) genuineness, purity, refinement.

- Postma translates the original Hanunoo-Mangyan language into “waters for the soul,” which again, probably is influenced by his real-life insight. This line makes me ask what exactly happened after the burial. Was it a burial cleaning? Was it a religious rite? Was it describing something more transcendent?

From the words given, “waters for the soul” has so many connotations to body, mind, and spirit. This led me to connect it to my own experiences.

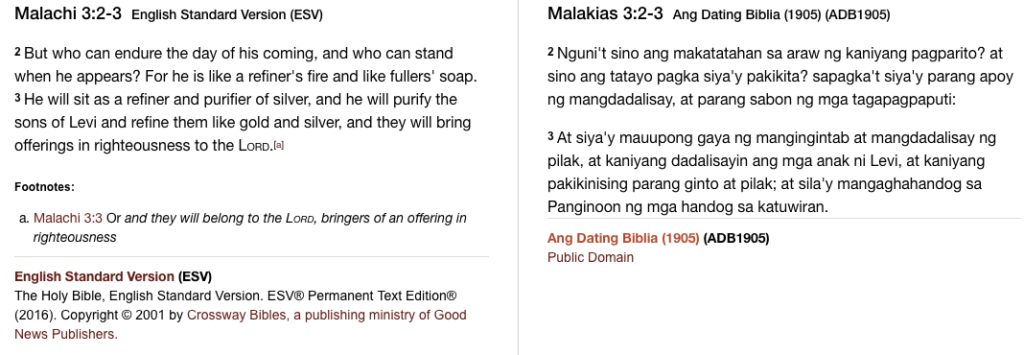

Refiner’s Fire

The word “dalisayan” reminded of a verse from Malachi that describe’s God’s love for us as a “refiner’s fire” (“apoy ng mangdadalisay“). God does not indiscriminately destroy but aims to purify and ultimately give us hope. If you read earlier in the book of Malachi, God begins with saying “I have loved you.” God’s aim is to complete his covenant of loving us, and part of that means to purify us.

And we need to be purified. From the above ambahan, you see that the purification part is the turn of the poem. The tone changes from suffering into rejoicing with family. If the author of that poem removed the lines about purification, I believe the poem wouldn’t be as poetically successful. The author does not show a lack of transition between the soul dying and then reuniting with family. The author makes it a point that he was “purified” in a “fining-pot” before his family reunion. “Dalisayan” is a word that suggests something more than the cessation of physical sickness or suffering. Something changed that was more than death.

A “fining-pot” or furnace, was used to melt metals and separate the gold or silver from the dross. Whatever you believe this “fining-pot” is in your life, it’s a beautiful thing, a poetic key— which is why I chose the word “dalisayan” to logograph into calligraphy.

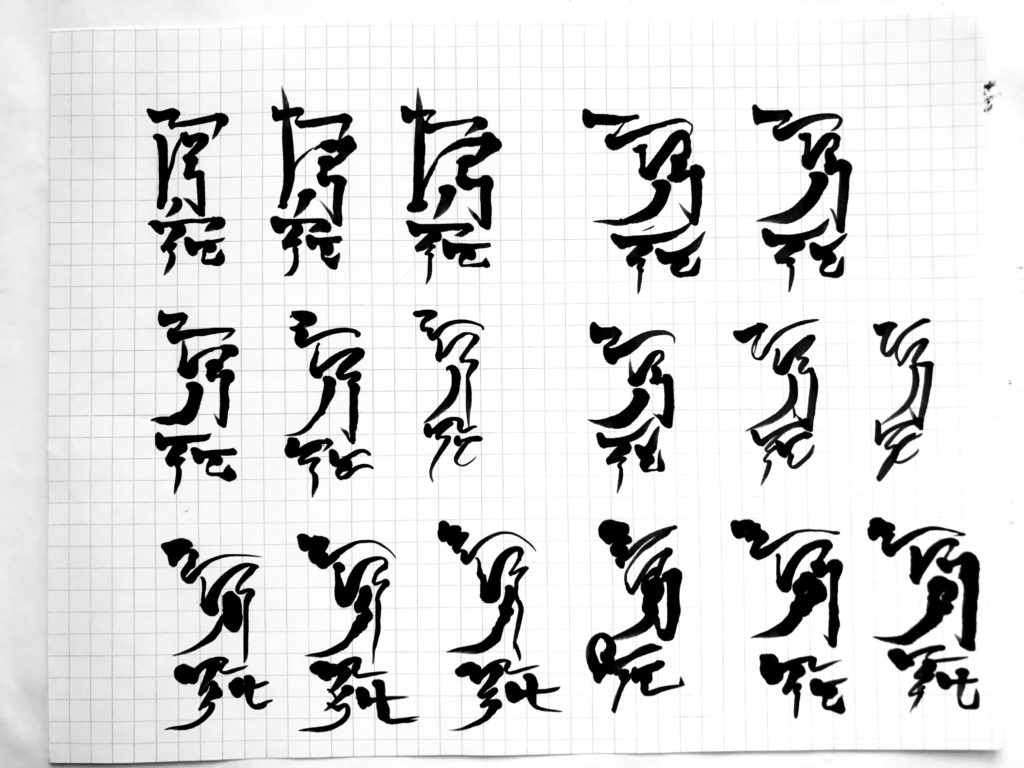

Logographing: Dalisayan

It was ridiculously fun figuring out a way to transform the Baybayin script of dalisayan into an aesthetic whole or Logogram (click for my definition). I am equally an amateur in translating Tagalog poetry as I am with calligraphy, but I find it so satisfying to learn day by day— the strokes, the strength, the pressure, the speed, and the spirit of the brush.

Filipinos, as far as I know, do not have a history of calligraphy. They traditionally carved poetry on bamboo tubes or slates. However, as weaknesses are tied to strengths— as an Asian-American and that I find ink and paper cool— in addition to the lack of history and precedent (that I know of)— I have the freedom to make the future of Baybayin script and calligraphy. Below is my work in transparency:

Links

- About Filipino burial ceremonies

- Sermons about refining fire

- See more Logographing and Baybayin Filipino calligraphy on my Instagram

Leave a Reply